Repeating Actions with Loops

Last updated on 2024-12-02 | Edit this page

Estimated time: 30 minutes

Overview

Questions

- How can I do the same operations on many different values?

Objectives

- Explain what a

forloop does. - Correctly write

forloops to repeat simple calculations. - Trace changes to a loop variable as the loop runs.

- Trace changes to other variables as they are updated by a

forloop.

Iterating over lists

An example task that we might want to repeat is accessing numbers in a list, which we will do by printing each number on a line of its own.

In Python, a list is basically an ordered collection of elements, and

every element has a unique number associated with it — its index. This

means that we can access elements in a list using their indices. For

example, we can get the first number in the list odds, by

using odds[0]. One way to print each number is to use four

print statements:

OUTPUT

1

3

5

7This is a terrible approach for three reasons:

Not scalable. Imagine you need to print a list that has \(N\) elements.

Difficult to maintain. If we want to format each printed element with an asterisk or any other character, we would have to change four lines of code. While this might not be a problem for small lists, it would definitely be a problem for longer ones.

Fragile. If we use it with a list that has more elements than what we initially envisioned, it will only display part of the list’s elements. A shorter list, on the other hand, will cause an error because it will be trying to display elements of the list that do not exist.

OUTPUT

1

3

5ERROR

---------------------------------------------------------------------------

IndexError Traceback (most recent call last)

<ipython-input-3-7974b6cdaf14> in <module>()

3 print(odds[1])

4 print(odds[2])

----> 5 print(odds[3])

IndexError: list index out of rangeHere’s a better approach: a for loop

OUTPUT

1

3

5

7This is shorter — certainly shorter than something that prints every number in a hundred-number list — and more robust as well:

OUTPUT

1

3

5

7

9

11The improved version uses a for loop to repeat an operation — in this case, printing — once for each thing in a sequence. The general form of a loop is:

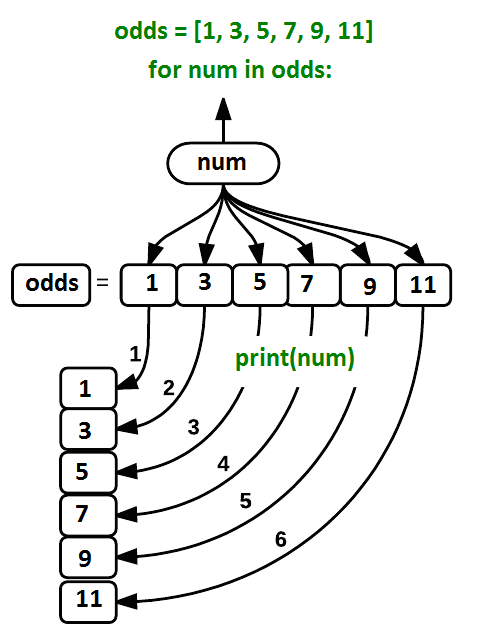

Using the odds example above, the loop might look like this:

where each number (num) in the variable

odds is looped through and printed one number after

another. The other numbers in the diagram denote which loop cycle the

number was printed in (1 being the first loop cycle, and 6 being the

final loop cycle).

We can call the loop

variable anything we like, but there must be a colon at

the end of the line starting the loop, and we must indent anything we

want to run inside the loop. Unlike many other languages,

there is no command to signify the end of the loop body

(e.g. end for); everything indented after the

for statement belongs to the loop.

What’s in a name?

In the example above, the loop variable was given the descriptive

name odd_number. We can choose any name we want for these

loop variables. We might just as easily have chosen the name

banana for the loop variable, as long as we use the same

name when we invoke the variable inside the loop:

OUTPUT

1

3

5

7

9

11It is a good idea to choose variable names that are meaningful, otherwise it would be more difficult to understand what the loop is doing.

Here’s another loop that repeatedly updates a variable:

PYTHON

length = 0

names = ['Curie', 'Noether', 'Turing']

for value in names:

length = length + 1

print(f'There are {length} names in the list.')OUTPUT

There are 3 names in the list.It’s worth tracing the execution of this little program step by step.

Since there are three names in names, the statement on line

4 will be executed three times. The first time around,

length is zero (the value assigned to it on line 1) and

value is Curie. The statement adds 1 to the

old value of length, producing 1, and updates

length to refer to that new value. The next time around,

value is Darwin and length is 1,

so length is updated to be 2. After one more update,

length is 3; since there is nothing left in

names for Python to process, the loop finishes and the

print function on line 5 tells us our final answer. We and

Python know the loop is over by line 5 because of the indenting of the

code block.

Note that a loop variable is a variable that is being used to record progress in a loop. It still exists after the loop is over, and we can re-use variables previously defined as loop variables as well:

PYTHON

name = 'Rosalind'

for name in ['Curie', 'Noether', 'Turing']:

print(name)

print(f'After the loop, `name` is set to {name}')OUTPUT

Curie

Noether

Turing

After the loop, `name` is set to TuringRecall also that finding the length of an object is such a common

operation that Python actually has a built-in function to do it called

len:

OUTPUT

4len is much faster than any function we could write

ourselves, and much easier to read than a two-line loop; it will also

give us the length of many other things that we haven’t met yet, so we

should always use it when we can.

Iterating over ranges

Python has a built-in function called range that

generates a sequence of numbers. range can accept 1, 2, or

3 parameters.

- If one parameter is given,

rangegenerates a sequence of that length, starting at zero and incrementing by 1. For example,range(3)produces the numbers0, 1, 2. - If two parameters are given,

rangestarts at the first and ends just before the second, incrementing by one. For example,range(2, 5)produces2, 3, 4. - If

rangeis given 3 parameters, it starts at the first one, ends just before the second one, and increments by the third one. For example,range(3, 10, 2)produces3, 5, 7, 9.

Summing a list

Write a loop that calculates the sum of elements in a list by adding

each element and printing the final value, so

[124, 402, 36] prints 562

Iterating over strings

In Python, any iterable object may be looped over. This, for example, includes the characters in a string.

The body of the loop is executed 6 times.

Using enumerate to iterate over lists

The built-in function enumerate takes a sequential

container object (e.g., a list) and

generates a new sequence of the same length. Each element of the new

sequence is a pair composed of the index (0, 1, 2,…) and the value from

the original sequence:

PYTHON

odds = [1,3,5,7]

for index, odd in enumerate(odds):

print(f'list_index={index} :: list_value={odd}')OUTPUT

list_index=0 :: list_value=1

list_index=1 :: list_value=3

list_index=2 :: list_value=5

list_index=3 :: list_value=7The code above loops through odds, assigning the index

to index and the value to odd.

Computing the Value of a Polynomial

Suppose you have encoded a polynomial as a list of coefficients in the following way: the first element is the constant term, the second element is the coefficient of the linear term, the third is the coefficient of the quadratic term, where the polynomial is of the form \(ax^0 + bx^1 + cx^2\).

OUTPUT

97Write a loop using enumerate(coefs) which computes the

value y of any polynomial, given x and

coefs.

List comprehensions

Often times we want to quickly generate a container object, like a

list. So far, our only method involves the append internal

method. Suppose we want to generate a list of the first five positive

odd numbers:

PYTHON

# create an empty list

odds = []

# loop over integers \in [0,4], append associated odd to odds list

for i in range(5):

odds.append(2*i+1)

# enumerate over the odds, which provides two loop variables, the

# incremental count from zero `i` and the associated list value `odd`

for i,odd in enumerate(odds):

print(f'{i} : {odd}')OUTPUT

0 : 1

1 : 3

2 : 5

3 : 7

4 : 9This is such a common task that most high-level languages — and even some low-level ones like Fortran — provide a syntactical sugar for quickly creating the same list, via list comprehension:

OUTPUT

0 : 1

1 : 3

2 : 5

3 : 7

4 : 9Dictionary comprehension

Similarly, if we wanted to create a dictionary via repetition, we

have the implied method of instantiating an empty object and appending

to it. But there is a nuance when comparing to list iteration:

dictionary objects do not work as expected with the

enumerate method. Instead we must access the

items() sub-method of the dictionary object,

PYTHON

squares = {}

for i in range(5):

squares[i] = i**2

for key,square in squares.items():

print(f'The square of {key} is {square}')OUTPUT

The square of 0 is 0

The square of 1 is 1

The square of 2 is 4

The square of 3 is 9

The square of 4 is 16A dictionary comprehension makes this all the more syntactically sweet:

PYTHON

squares = {i:i**2 for i in range(5)}

for key,square in squares.items():

print(f'The square of {key} is {square}')OUTPUT

The square of 0 is 0

The square of 1 is 1

The square of 2 is 4

The square of 3 is 9

The square of 4 is 16There are also the submethods of keys() and

values() for times when both pairs are unneeded.

Monitoring loop progress

Often times in scientific computing, the majority of a program’s

execution will occur within a loop. For example, when solving a system

of partial or ordinary differential equations, solvers typically must

iteratively step forward in time. Without periodic reporting or

indication of the loop’s status, it may feel like the program will never

end. (We will see examples of this after the upcoming numpy

and plotting lessons.) But for now it’s important to emphasize the

existence of an extremely convenient external third-party module that

provides rich progress bars for loops, tqdm:

OUTPUT

42%|████████████ | 4233/10000 [00:03<00:04, 1183.17it/s]]- Use

for variable in sequenceto process the elements of a sequence one at a time. - The body of a

forloop must be indented. - Use

len(thing)to determine the length of something that contains other values. - Use

enumerateto obtain loop variables for a sequential object’s indices and values. - List and dictionary comprehensions provide a fast and convent way to initialize those objects.

- Use the

tqdmmodule to create rich progress bars that give a better indication of the loop’s status and provide rough benchmarks.